Panchayati raj of Himachal Pradesh:-

Himachal came into being in the year 1948. It was a Chief Commissioner’s province. It enjoyed Part “C” State’s status under the Constitution. It had no legislative body of its own. A beginning was made in 1949, to introduce PR in Himachal Pradesh. The state therefore, adopted Punjab Village Panchayat Act of 1839. As a consequence in the year 1949, in Himachal Pradesh, 132 panchayats were established. There were only four districts in Himachal Pradesh in 1949. The number of Panchayats in each district was: Mahasu (45), Mandi (33), Chamba (54), Sirmour (54). Gram Panchayats (GP) in Himachal Pradesh (HP) were established in the year 1952 for the first time in a regular fashion under the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act 1952. In 1953 some six hundred GPs and equal number of Nayaya Panchayats (NP) were formed later on. At the same time, at the block level, Block Development Advisory Committees (BDAC) were established. After the integration of Punjab Hill Areas, the number of Panchayats rose to 1900. Gram Sabha in Himachal Pradesh hardly met to discuss any issue.It is some times maintained that before the formation of Himachal Pradesh as a Part “C” State, there was no regular PR system under any legislation in any of the integrated states. But it is difficult to believe this assertion as it is not corroborated by facts. In the areas now forming Bilaspur, Sirmour, Lahaul Spiti, Kullu, Kangra districts, etc. some regularly established form of PR was in operation even before 1949. Similarly in Sirmaur State, before independence, the Punjab Panchayati Raj Act, 1939 was already in force. In Bilaspur State (erstwhile a princely state) between 1947 to 1954, there were Halqa and Pargana (a block level unit of administration) councils each having Pradhan, Up-Pradhan and a Secretary. The Pargana Councils more or less perfornied those very functions which are now being performed by the Panchayat Samitis (PSs). The Pargana Councils hardly functioned for about one year and thereafter the Punjab Panchayat Act, 1939 was extended to Bilaspur state (1950). Before independence, Panchayats existed in Lahaul Spiti in addition to those in the princely states of Bilaspur and Sirmaur. Thus in most of the areas of Himachal Pradesh, traditional panchayats were in operation. In some of the areas, the Punjab Village Panchayat Act of 1939 had already been introduced and Panchayats were successfully functioning. This Act, being the first statute of rural government in some areas of present Himachal Pradesh (HP), was instrumental in laying the strong foundations of PR till 1952, when the State passed its own PR legislation. With a view to bringing the working of panchayats in accordance with local conditions and growing aspirations of the people for  democratization at the village level, the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act (Act No. 6 of 1953) was passed in 1952 by Himachal Pradesh Vidhan Sabha, and it came into operation in the year of 1954, when Panchayats were established in the State.Under this Act, the principle of election on adult sufferage was accepted and gram panchayats were established in the whole of the Pradesh, one in each Patwari circle. Under this Act, 466 village panchayats were constituted in 1954, their number increased to 497 due to the reorganisation of panchayat circles in Chamba district and Chini Tehsil of Mahasu district’, and further to 638 in 1962.’° The special feature of this Act was that a three-tier PR system was introduced in the state. There were 26 Tehsil Panchayats and 3 Zila Panchayats. The Tehsil and Zila Panchayats were established through indirect elections. The Act was mainly drafted on the basis of Uttar Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act, 1948, although Panchayat legislations of other states were also reviewed and taken into consideration. The rural government system did not work effectively during the fifties mainly due to the apathy of sarpanches, inadequacy of powers, lack of consciousness, poor literacy rate, caste distinction, domination of males and lack of proper publicity of panchayat programmes.” The situation was the same in the other parts of the country. In the case of Himachal Pradesh a genuine step towards the re-introduction of PR in Himachal Pradesh was taken in 1968. Earlier when the hilly areas of Punjab were handed over to Himachal in 1966, and it had become almost certain that increase in the area, population and greater administrative responsibility would fulfil the long cherished demand for statehood.

democratization at the village level, the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act (Act No. 6 of 1953) was passed in 1952 by Himachal Pradesh Vidhan Sabha, and it came into operation in the year of 1954, when Panchayats were established in the State.Under this Act, the principle of election on adult sufferage was accepted and gram panchayats were established in the whole of the Pradesh, one in each Patwari circle. Under this Act, 466 village panchayats were constituted in 1954, their number increased to 497 due to the reorganisation of panchayat circles in Chamba district and Chini Tehsil of Mahasu district’, and further to 638 in 1962.’° The special feature of this Act was that a three-tier PR system was introduced in the state. There were 26 Tehsil Panchayats and 3 Zila Panchayats. The Tehsil and Zila Panchayats were established through indirect elections. The Act was mainly drafted on the basis of Uttar Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act, 1948, although Panchayat legislations of other states were also reviewed and taken into consideration. The rural government system did not work effectively during the fifties mainly due to the apathy of sarpanches, inadequacy of powers, lack of consciousness, poor literacy rate, caste distinction, domination of males and lack of proper publicity of panchayat programmes.” The situation was the same in the other parts of the country. In the case of Himachal Pradesh a genuine step towards the re-introduction of PR in Himachal Pradesh was taken in 1968. Earlier when the hilly areas of Punjab were handed over to Himachal in 1966, and it had become almost certain that increase in the area, population and greater administrative responsibility would fulfil the long cherished demand for statehood.

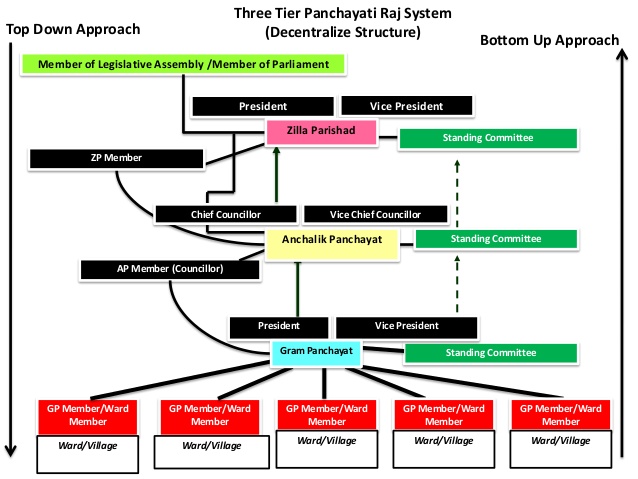

In 1968 statutory position was given to the PR bodies in Himachal Pradesh. The Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act, 1968, was introduced w.e.f. November 15th, 1970 and provided for a three-tier system of PR, i.e. Gram Panchayat at village level, Panchayat Samiti at the block level and Zila Parishad at the district level.

Main objectives of the Act were:

(a) To consolidate and amend laws relating to PRIs;

(b) To provide for the constitution of PR bodies in the entire Union Territory of

Himachal Pradesh;

(c) To provide for a uniform pattern of PR institutions in both the old as well as the newly merged areas of Punjab in Himachal Pradesh;

The Himachal Panchayati Raj Act, 1968 under Section 18(1) earmarked about twenty seven administrative duties., for the GPs. These statutory duties were required to be performed by GPs subject to the limit of funds at their disposal. The funds made available to the GP were extremely limited, due to which they failed to perform the assigned duties. In the field of election, according to PR Act 1968, all the members of GP were elected directly by the members of Gram Sabha (GS) from amongst themselves. The Pradhan of GP was also elected directly and there also existed a post of up-Pradhan. The GP was normally elected for the period of five years. However, after 1962 election of panchayats were held in 1972. It was the third election of PR bodies in the state. After the election of 1972 there were 2038 Gram Panchayats and equal number of Nayaya Panchayats (NP) were set up. Nayaya Panchayats were functioning in the state for discharging the judicial functions up to March 1978. But with the enforcement of Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj (Amendment) Act 1977, the NP stood abolished and judicial functions were assigned to Gram Panchayat. In 1988 subsequently the PR Act was amended and provision for payment of honorarium to the chairman and Vice-Chairman of Panchayat Samiti (PS) and for Pradhan and Up-Pradhan of Gram Panchayat was included in the Act. Further this amendment provided for among other things, assured existence and constitution of GP, PS, and reservation of seats for SC and thirty per cent reservation for women Panches at Gram Panchayat level, twenty five to thirty per cent reservation of seats for SCs. Since 1952, the first election to GPs was held in the year 1954, second after eight years in 1962, and third after a gap of ten years in 1972, and fourth in 1978. The fifth election was held in September 1985 and before the 73rd Amendment the sixth election for PR bodies held in 1992. Nearly eighty five per cent of people live in the villages of Himachal Pradesh. Here PR bodies have enjoyed special status since beginning. Despite occasional deliberate attempt to throttle them, the PRIs have survived, though with negligible powers. GPs and PS occupy special status of prime importance. The offices of the Panches and Pradhans are coveted and people attach more importance to Pradhans and Chairmen because governmental agencies and officers on their visits to village and block or otherwise contact Pradhans and Chairmen of PSs whenever needed. The official recognition raises their social status and power. Other factors which affect the PR membership are the economic status of the individual and family. It appears that since beginning (after independence) the persons having strong economic background are acceptable to political parties and become Pradhans and Chairmen. Either castes group leaders, rich individuals or popular caste groups leaders or popular social workers are favoured in panchayat elections. In most of the cases rich people are preferred as leaders for PRIs. Another more important factor is the political factor. Politics is the central factor which provides a prestigious, honourable and independent status to PRIs in the state. As and when a political decision has to be taken it has to be with the active consent and support of political parties either in the Parliament or in the state legislature to decentralize more powers to PR bodies, remove bureaucratic controls, provide constitutional status, statutorily providing regular holdings of elections, make provisions for sufficient funds to be made at the disposal of these bodies. All these questions are to be decided by political institutions. Whatever status that the PRI’s will have to enjoy, shall be subject to the dictates of constitution of India and Acts passed by the state legislature. No doubt 73rd Amendment in Indian Constitution provided Constitutional status to PRIs, still the fate of PRIs depends on the state governments’ attitude towards them. The Balwant Rai Mehta Committee Report had little impact on the Panchayati Raj Act of Himachal Pradesh, as three-tier institutions were already functioning in the state. Cooption of women and scheduled castes in GPs of the state and the provision of indirect election of primary members of PSs was already a feature of PRIs in Himachal Pradesh. The other important committee on PRIs, constituted by Janta Government, was known as Ashok Mehta Committee. This committee had also little impact on the PRIs in Himachal Pradesh because it is the state where an impression has been created that it is the best administered state in North India. This impression has been the creation of bureaucracy which enjoy enormous powers, because the political elite in comparison to them, is less educated, less knowledgeable, less dynamic, less articulate, less mobile and less worldly wise. Intellectual level of political elite in Himachal Pradesh is far inferior to the administrative strata. Hence before the 73rd amendment the condition of the PRIs was poor. The philosophy of Himachal Pradesh Government till the year 1967-68 was, “The decentralisation of power to the grass root level should be minimal. Whatever powers is decentralized and functions transferred, should be subject to prior approval, consent and consultation of district collector as well as his subordinates. The over all control and supervision over the PRIs shall be exercised by the Director of Panchayats, District Panchayat Officer (DPO) and their field officers and the Panchayat inspectors.”” Due to such attitude the purpose of “government of the people, to the people and by the people” was defeated by making a group of bureaucrats every second knocking at the door of Gram Panchayats or Panchayat Samitis with a warning rod. like a police inspector. Thus Panchayati Raj in Himachal Pradesh remained bureaucrats’ self government instead of rural self government till the 73rd Constitutional Amendment. The major causes of the decline and impoverishment of PRIs in Himachal Pradesh after the last sixties were as follow:

- Non-availability of finances required to perform assigned statutory functions and duties;

- Large scale supersession of panchayats and panchayat samitis in the state;

- Withholding of panchayat elections;.

- Unfounded fears in the minds of ministers and MLAs about the potential loss

of political power, prestige and influence in case, chairmen Zila Prishad and Panchayat Samitis get themselves entrenched in local politics;

- Bureaucratic apathy against Zila Parishads (ZPs) and their functioning because of psychological barriers and unwillingness on the part of district level bureaucrats to accountable to Chairman of Zila Parishad;

- Catastrophic change in the constitutional status of Himachal Pradesh;

- Absence of separation of a special component plan for PRIs with forty per cent of the total state expenditure;

- Absence of constitutional status to PRIs;

- Absence of a provision to statutorily require the district collector to hold

elections to PRIs within specified time;

- Absence of a “Panchayati Raj Fund” out of which PRIs of a state could get funds on nominal interest to spearhead their development activities.

On the basis of above points it can be concluded that PRIs in Himachal Pradesh before 73rd Amendment were mere agencies of the Centre and State Governments to implement the developmental programmes and schemes so PRIs did not enjoy any real power to govern the rural Himachal. According to the various studies, under the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act 1968, the real powers were vested by the Act in the District Collector, Sub-Divisional Magistrate and the Director Panchayati Raj Department. The slogan of “democratic decentralization” was a hoax and far cry. There was no “real power” available either to Pradhans of Gram Panchayats or to Chairmen of the Panchayat Samitis. Every section of Panchayati Raj Act, 1968, whether it was related to power, duties, functions or taxation power of GPs or PSs, required prior approval or sanction of State Government, i.e. Director Panchayats or District Collector. It appears that PRIs in Himachal Pradesh had been crippled due to utter ignorance and sheer intellectual bankruptcy of the political leadership in the years when this statute was passed. Functionally, a two-tier system had been handicapped because of excessive requirements made by the statute to chain a Gram Panchayat and a Panchayat Samiti to the wishes and directions of district or state bureaucrats. The Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act, 1968, and its implementation gave hegemonic position to the bureaucracy from village to the district level. The most important servant having to do with Panchayati Raj at grassroots level (Gram Sabha/Panchayat) was secretary of Gram Panchayat or a group of Panchayats to be appointed by the Director of Panchayats. Thus he was the state servant and had loyalty towards the state administration. The Gram Panchayats were empowered to make such appointment as considered necessary. But under the Act these servants thus appointed may be suspended, dismissed or punished by the Gram Panchayat who may make remuneration to such servants out of Gram Sabha funds. But they will work according to the rules framed by state government. In the Act the Gram Panchayats were empowered to conduct enquiries against some government servants. But the superior position was given to bureaucracy. The HPPR Act 1968, required conduct of enquiry by the GPs against twelve specifically mentioned government servants to which government had extension of provisions of the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act, 1968 and to submit a report with a prima facie evidence to concerned superior officer or to the Deputy Commissioner or S.D.O. In the field of financial matters the position of GP was insignificant. All the powers were with the bureaucracy. Through financial matters state government made direct encroachment in areas of GP under the Act. Prior approval had to be obtained from the Deputy Commissioner for undertaking any work of more than five hundred rupees. In the field of taxation GP had to take prior approval of D.C. -Tlius Himachal Pradesh Government up to early nineties had made Panchayati Raj virtually captive of and perennially at the mercy of D.C. and the SDM. In a democratic set-up it was irony that democratically elected members of PR could be removed by a civil servant. In the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act 1968 such Other provisions were also kept by which bureaucracy interfered and made inroads into the working of PRIs. Such sections of the Act were:

- The Act provided delegation of powers by the state government to the Director Panchayats (except the powers to make rules).”

- The government retained its discretionary power to direct the holding of election of the members of Executive Committees of all Sabhas.

- The Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act 1968 empowered a DC or SDO to

order in writing to suspend the execution of a resolution or order of a GP or prohibit the doing of any act.

Thus in field of governance PRIs had no real power. Virtually under the Act state was governed by the bureaucrats from bottom to top. In the field of revenue, a Gram Sabha under Section 41 of the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act, 1968 had different sources of income as given below:

- All grants from government and local authorities,

- the balance if any standing at the credit of Panchayat,

- the balance and proceeds of all funds, which in the opinion of the collector, were or are being collected for common secular purposes of the village,

- ail donations,

- all taxes, duties, cesses and fees imposed and realized under this Act,

- the sale proceeds of all dust, dung or refuse,

- income derived from common lands vested in the panchayat under any law for the time being in forcesi!

The Gram Panchayats were authorised to impose house tax under the 1968 Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act. But the tax income was meagre source of income. The Gram Panchayats were poorly equipped to perform even petty civic functions. Before the 73rd amendment panchayats had very limited sources of income. They had very limited powers of taxation and were more or less dependent upon the centre and state grants.

Functioning of Panchayati Raj Institutions in Himachal Pradesh Impact of Caste and Class Factors (Before 73rd Amendment):

In large part of Himachal Pradesh, due to its adverse geo-physical features, remained less exposed to the modern culture. Its own traditional culture still dominates the modern democratic institutions. Caste as well as class is the dominating factor in the political field. Prior to the 73rd Amendment of the Constitution various research studies were conducted in the different parts of the Old and New Himachal. The study conducted by Sud revealed that in Kangra district Rajput and Brahmins dominated the PRIs and in district Shimla also Rajputs dominated the PRI another case study of six sample villages of Dangri Panchayat of Solan district revealed a closed hierarchically caste-ridden structure based upon ascription rather than achievement, and an economic structure based upon subsistent stagnant agriculture having low inputs and limited output. The study concluded that “leadership was confined to upper castes and within these castes to affluent individuals. Thus prior to 73rd amendment the caste played its traditional role in the functioning of panchayats and the scheduled castes still remained disadvantaged groups. Not only the electoral behaviour of the rural people was dominated by the traditional institutions, but the functioning of PRIs also had its own distinguished features. It was substantiated in the study of Sud in respect of Kangra district. Generally most influential persons manned traditional panchayats. They either belonged to such caste as has majority in the village or they are the persons who are economically sound. Even the elected Pradhans act upon the advice of the traditional panchayat.” Apart from the hold of traditional panchayats in the Panchayati Raj institutions, the village politics too is caste-ridden but these loyalties remain like a hidden current. Apparently people refrain from publicizing caste alliances but caste factor dominates the electoral behaviour as well as the outcomes of the decision making process of the Panchayati Raj institutions. Yet another case study conducted by Sharma brought out that, “Caste plays an important role in the panchayat elections; politicians and political parties are mobilizing caste groups and are identifying themselves with them in order to organize their power in these caste factions which are in the process of transformation. Thus the caste was a dominating factor in Himachal Pradesh and political parties also attached greater importance to the caste politics in Himachal Pradesh. Upper castes played dominating role in the PRIs. One study strengthens the view that seven out of eight members of Juni Panchayat (Tehsil Sunni) belonged to upper caste Rajputs and Brahmins sharing three positions each. High caste dominance was too obvious as the office of Pradhan had never been occupied by a lower caste member. The scheduled castes suffer from a disadvantage as more cases before Panchayat as a court, were brought against them by the higher castes. Higher castes were involved in litigations more than the lower castes. However, none of the scheduled castes respondents complained of caste bias in the working of Panchayat.

Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act, 1994 :-

With a view to bringing the law relating to the PRIs in conformity with the provisions

of Constitutional Seventy Third Amendment, the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj

Act, 1994 was enacted on 23 January 1994 and came into force w.e.f. 23 April 1994.

Its salient features are as under:

Gram Sabha: The Gram Sabha is the first modern political institution which seeks to place direct power in the hands of the people. The legislative empowerment of the Gram Sabha in India is a political development of utmost importance, because it marks the clearest break from the most dominant political orthodoxy in this century. Under Section 3 of the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act 1994, a Gram Sabha is constituted for a village or a group of contiguous villages with a population of less than one thousand and not exceeding five thousand. The government can relax these limits in particular case. The Gram Sabha once established, can be reorganised by the government by including or excluding any area from its jurisdiction. Every person who has attained the age of eighteen years within tine Gram Sabha area entitled to be the voter of Gram Sabha.

Meetings: Prior to the coming into being of HPPR (Second Amendment) Act, 2000 every Gram Sabha was required to hold two general meetings in each year one in the summer and the other in winter season. Later the number of general eetings in an year was increased to four. It is the responsibility of the Pradhan to convene the meetings of Gram Sabha.

Quorum: The quorum of Gram Sabha’s general meetings which was one-fifth of the total members of Gram Sabha as per the 1994 Act, was changed to one-third under the HPPR (Second Amendment) Act 2000. Decisions are taken by the majority of members present and voting.

Up-Gram Sabha: The HPPR (Second Amendment) Act, 2000 made provision for the setting up of Up-Gram Sabha for each ward of the Gram Sabha, The person representing the ward as a member of Gram Panchayat is enjoined upon to convene and preside over two general meetings of Up-Gram Sabha every year. The Up-Gram Sabha nominates its representatives for General Meeting of Gram Sabha one-third of whom have to be women. It is empowered to take cognizance of disputes in its area and make recommendations to Gram Sabha.

Functions of the Gram Sabha: Under Section 7 of Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj

Act, 1994, Gram Sabha has been assigned many functions. For example, it mobilises

voluntary labour and contribution in kind and cash for the community welfare

programmes. It identifies the beneficiaries for the implementation of development

schemes pertaining to the village, promotes unity and harmony among all sections of

society in Sabha area and is vested with the power to consider and make

recommendations to Gram Panchayat on important matters. Thus Gram Sabha works

as the legislature of village. Regarding the PRIs system.

Gram Panchayat: Gram Panchayat is the lowest tier of PR. It is the executive committee of the Gram Sabha. This executive committee is elected by the Gram Sabha to execute its works and programmes. Under Section 8 of the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act 1994, for a population not exceeding 1500 a Gram Panchayat have five members, between 1500 to 2500 it will have seven members. between 2500 to 3500 nine members, between 3500 to 4500 eleven members, and above 4500 thirteen member. It is also provided further that the number of members of a gram panchayat, excluding Pradhan and up-Pradhan, shall be determined in such a way that the ratios between the population of Gram Sabha nd the number of seats of members in such a panchayat to be filled by the election shall, so far as practicable, be the same throughout the Sabha area.

Developments in Panchayati Raj After the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act 94 :-

In 1997, to bring the provisions of the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj Act, 1994 in lune with the provision of the Panchayats (Extension to the Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 enacted Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj (Second Amendment) Act 1997, Chapter VI-A have been added in the original Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj, Act 1994. According to the Himachal Pradesh Panchayati Raj (Second Amendment) Act, 1997 the provisions of chapter VI-A will be apply to PRIs in the scheduled areas of the state. This Act extended the role of Gram Sabha and gave list of it’s functions. Besides the approval of economic and social plan. Gram Sabha will be responsible for the identification of beneficiaries under poverty alleviation and other programmes. Under the Act Gram Panchayat will be responsible to Gram Sabha for the proper utilisation of funds. Further the Act provides for the special provision of reservation for scheduled tribes in all PRIs. To preserve the traditions values and customs in the tribal areas Gram Sabha has been assigned wide functions such as:

(a) the ownership of minor produce;

(b) enforcement of prohibition or regulation or restriction of the sale and consumption of any intoxicant;

(c) management of village markets by whatever name called;

(d) exercising control over money lending in the scheduled tribes.

Above functions will be performed by the Gram Sabha with the help of village in scheduled areas.

The Panchayat Samiti will perform the functions related to:

(a) exercising control over institutions and functionaries in all social sectors;

(b) control over local plans and resources for such plans including tribal plans.

Thus the legislative empowerment of the Gram Sabha is a political development of utmost importance, because it marks the clearest break from the most dominant political orthodoxy of this century. Further to make the PRIs more effective, HPPR (Amendment) Act 2000 was enacted. This Act extended the powers of panchayats to impose penalty under the section 11 and 12 of the HPPR Act, 1994. The Act provides the provision that total 1/3 seats reserved for SCs/STs in a village shall be occupied by the women. The Act provided that if the office of the Chairman or Vice-Chairman falls vacant due to certain reasons a fresh election within a period of two months from the date of occurrence of vacancy shall be held from the same category, in the prescribed manner. In the case of standing committee, the term will be two and a half years. To eliminate corruption from the PRIs amendment has been made in Article 122 to debar the person from contesting election, if he is involved in corrupt practices. In 2000 again, HPPR Act, 1994 was amended second time in a year and in this Act provisions are made for quarterly meeting of Gram Sabha (first Sunday of January, April, June and October). Quorum of the meetings will be one-third families of the total panchayat. Important provision regarding the Up-Gram Sabha has been added. Annually two meeting will be held and the meetings will be presided over by the ward member (Panch) regarding Panchayats, in the event of occurrence of casual vacancies in a panchayat to the extent the number of remaining elected office bearers do not fulfil the quorum required for convening a meeting of the panchayat then the State Government or prescribed authority may nominate persons to fill the casual vacancies occurred in a Panchayat till new members are elected in accordance with the provision of the HPPR Act, 1994. In the field of social and economic planning now Panchayats will directly submit their development plan to District Planning Committees (DPCs). Now the District Planning Committees will be presided over by a minister to be chosen by the State Government under the Second Amendment Act 2000.”